How Arnie Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Asteroid

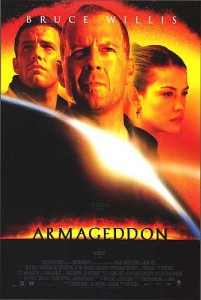

I’ve often referenced Armageddon on Now Playing Podcast, and, shockingly, those comparisons are usually favorable. This has led to many a raised eyebrow and gentle mocking — even from co-hosts who have never seen Michael Bay’s 1998 blockbuster (you know who you are).

So, though 1998 contained many movies that influenced me, from Bride of Chucky to Pi to Your Friends and Neighbors to Very Bad Things, I think I must take the opportunity to discuss Armageddon and explain how Bay changed my perception of action films.

If it helps you to relate to my position at all, I’ll admit that I was skeptical about the movie going in.

First, it was the second giant-rock-destroys-Earth movie of 1998 (it was a comet in Deep Impact). Believe it or not, this idea had been one that petrified me for nearly a decade.

In 1990 I read an article in the newspaper entitled “The Doomsday Rock” which described the likelihood that, eventually, a giant asteroid would collide with Earth and cause the extinction of the human race.

I had grown up with the fear of nuclear Armageddon ending our species, but by 1990 the Cold War was over and I could finally stop worrying. Now came an even bigger fear — at least nuclear war required two human beings to consciously kill everyone, but no one could control or stop a giant asteroid.

I kid you not; I didn’t sleep for days after reading that article. It became my biggest fear: death by asteroid. It’s a terror I’ve learned to live with, but every day I hope that NASA receives the funding it needs to track more of these objects in space; as even NASA’s chief Charles Bolden has said our only current hope is to “pray.”

While the concept was one that scared me, seeing two similar movies came out in the summer of 1998 seemed excessive. Deep Impact beat Armageddon to theaters by more than two months, and it was a deeply moving and touching film. By the time of Armageddon’s debut I thought we’d already seen all the giant rock movies we needed.

Before seeing Armageddon I could not imagine why an astronaut would need a gun. It’s one of the many improbable plot twists that I ended up going with.

Even more than that, Armageddon‘s pre-release press made the film sound absurd. While ostensibly a disaster film about a big asteroid, I read articles which mentioned scenes showcasing astronauts with handguns. In what world would a gun become instrumental when a giant rock is about to kill all life on Earth? Despite having Bruce Willis as the star, this wasn’t Die Hard; what role would guns play? The astronauts in Deep Impact didn’t need them.

Despite those reservations I still found myself in a packed theater during the film’s Fourth of July opening weekend.

I was drawn in by several factors, starting with director Michael Bay.

Bay had impressed me with Bad Boys, which I thought was the best buddy-cop film since Lethal Weapon, and it marked the first time I saw Will Smith as a movie star. Bay’s follow-up, The Rock, was loud and heavy on explosions, but had some great action scenes for Sean Connery and Nicolas Cage.

And, for the longest time, I thought Bay also directed Cage in Con Air, which was dumb fun. I was likely confused by the fact that Jerry Bruckheimer produced both films. So, despite Bay having no involvement in Con Air, it was still a factor in my seeing Armageddon.

A larger factor pulling me to the theater was the cast. I had been a devout fan of Willis since Moonlighting. I loved seeing him in film; it didn’t matter if it was Color of Night, North, Pulp Fiction, Nobody’s Fool, or even Hudson Hawk.

Next was Ben Affleck, an actor I knew from his work with Kevin Smith, plus his Oscar-winning screenplay for Good Will Hunting. This was his first big-budget epic, and as he was a friend of Smith’s I was rooting for his success.

The rest of the cast — the ragtag group of asteroid drillers — was made up of some of Hollywood’s best 90s character actors, including Billy Bob Thornton, Steve Buscemi, Michael Clarke Duncan, Owen Wilson, and Keith David. I was even happy to see Ken Hudson Campbell, an actor I fondly remembered from his role as the “Animal” emotion in Herman’s Head.

While many of those stars would be launched to greater fame by Armageddon, even in 1998 I thought of this as a “dream team” of performers.

It was very lucky that I did know this cast, as I quickly realized that in Armageddon they were not characters, they were “types.” Affleck was the young hotshot, Buscemi the sardonic genius, Wilson the funny one, Duncan was the big guy who was soft on the inside, and Willis was the tough-as-nails, no-nonsense leader of the pack.

The baggage I brought with me from previous films helped me tremendously, as Armageddon wasn’t going to spend a lot of time developing new relationships or exploring character emotions. This movie was going to put the pedal to the metal and go, go, go.

It opens with a meteor shower demolishing New York City, and from that moment NASA is racing the clock to save humanity. The pace is so fast, Bay never stops the film to let the audience catch its collective breath.

Initially I was put-off by this; here was a movie exploring my deepest fear, yet the characters on screen never worried. They’re laughing, drinking, going to strip clubs and spending money like there’s no tomorrow — because there might not be. What a tonal shift from the dour Deep Impact. Even when we weren’t dealing with the asteroid directly, there were few scenes that didn’t involve a fight or a chase.

When we are introduced to Willis’ Harry Stamper he’s chasing Affleck through an oil-drilling platform, the older man shooting at the younger one. The reason for this homicidal rage? Affleck’s character, A.J., was caught sleeping with Harry’s daughter, Grace (Liv Tyler), and Harry hoped she would do better than a roughneck like her father.

It’s silly. It’s outrageous. It’s over-the-top. I wasn’t sure if I was going with it at all. My consternation only increased as the movie continued through the training montage and other silliness.

It wasn’t the concept of “only the best oil drillers in the world can save us” that put me off. That was standard fish-out-of-water storytelling. Think back to The Last Starfighter, where only a teenage video game player can win an interstellar war. Or in 48 Hours, where a cop needs a convict to catch a killer. Even in The Terminator a waitress had to fight alongside a warrior. This “you’re the only one, even though you’re unqualified” trope was one I’d grown up with, though never witnessed to this extreme.

My problem was I had no idea who these characters were. In a rare slow scene A.J. and Grace enjoy a final picnic, and some erotic animal cracker play, before his spaceflight. When asked if he thinks anyone else is doing that same thing at that time, A.J. responds, “I hope so. Otherwise, what the hell are we trying to save?”

It was a question that resonated with me — in a film full of cardboard characters, why did I care if everyone died?

It started to click, though, in another pre-spaceflight scene. Driller Chick (Will Patton) goes to see his ex and their son. The son doesn’t know his daddy, and a dropped line about a court order implies Chick hasn’t been the best father. But in this moment, at the end of the world, Chick wants to give his son a toy space shuttle. This was a character with very little screen time and no distinguishing characteristics, yet, out of the blue, suddenly he has a backstory: a son, and his own regret.

This is when I had my “eureka” moment. How many times have I seen this story of the estranged father who, just before a moment of heroism, reconnects with his child? Or vice versa? It’s a moment intended to endear us to the character and show an emotional connection, a reason for them to live, or motivation for them to sacrifice themselves.

Be it Nancy saying goodnight to her mother in A Nightmare on Elm Street, Arnold Schwarzenegger’s tender reconnection with Alyssa Milano in Commando, or even Willis’ own Die Hard where he leaves a message of regret for his wife and children, we’ve seen this time and time again. (We’d see an echo of it later in Armageddon between Harry and Grace as well).

The difference is that in those other films the moment is the climax of an emotional relationship, recognition of clarity and regret. But for Chick this is the first sign of characterization he’s given. Did we know he was a bad dad before this second? Did we care?

Through Chick’s sudden storyline I realized this wasn’t a film in the classic sense, it was a two-and-a-half hour music video. The vibe is the same — rollicking rock music (mostly classic rock by ZZ Top and Aerosmith) blared through the theater’s sound system while the characters underwent mental health evaluations and simulated spacewalks.

There were so many Aerosmith songs I wondered if the band (fronted by Liv Tyler’s father Steven) was chosen because Liv was in the movie, or if Liv was in the movie in exchange for Bay being able to raid Aerosmith’s catalog.

Even when the characters go to space and the rock music stops, the bombastic score takes over and keeps the vibe going. But more than just being driven by music, the storytelling methods in a short video and Armageddon are identical.

In a five-minute song there is little time to create a unique character, so tropes and types must be utilized to tell a story.

In Michael Jackson’s “Beat It” I don’t need to know the gang members have families and loved ones, I can bring that to the story myself. In Aerosmith’s “Cryin’” video I don’t need to hear a word to understand Alicia Silverstone is a rebellious teen. I didn’t need to see the kid picked on in school to know he’s a geek in the video for The Offspring’s “Pretty Fly for a White Guy.”

Bay came from music videos, and he trusts the audience to be used to this shorthand storytelling and rapid cutting. This movie was aimed directly at those weaned on MTV. If we have already seen scads of movies that embody a trope, why recreate it?

That’s when it hit me; Bay wasn’t lazy, he was efficient! He trusts his audience to have seen movies with these characters in them before, and thus he can actually get away with just putting tropes in a scene and letting them have their action. Characters can be types instead of people, in a movie that isn’t really about the people anyway.

I already hear, in my own head, the counter of that — that movies should be about people, and that if we don’t care about the characters how can we be excited by the action. It’s an argument I’ve used myself when discussing some of Bay’s later Transformers films.

Yet, I do believe that there should be balance. If all movies were the same, a cinema would be a mighty dull place to visit. There should be room for different types of stories. While two 1998 films told the story of a calamitous collision that ends life on Earth, the way the stories were told make those films as different as night and day.

But, and I cannot stress this enough, what Bay is doing is a tightrope walk. It is a dangerous game to rely solely on hackneyed plots and character tropes. Here, he pulls it off, in large part due to an extraordinarily likable, talented cast that brings more to the screen than they were given on the page.

The director must be given credit here as well. The editing, camerawork, and special effects were all top-notch. Bay knew how to film a scene for maximum adrenaline, and the music made it feel like a party.

Bay’s go-to image for pride is a giant American flag. It’s not subtle, but there’s no denying it plays in the heartland.

Who knew the end of the world could be so fun?

The film does overstay its welcome, especially in the longer Criterion Collection Director’s Cut where Chick’s same story beat is repeated with Harry visiting his father in a nursing home. Yet, for all the crazy twists and turns the plot takes — and the obvious heartstring-tugging climax — Armageddon is a fun ride. I walked out of it knowing I enjoyed the movie, though I didn’t respect it very much.

As Bay has continued to make movies Armageddon has become harder to defend. With three abysmal Transformers films, plus Pearl Harbor, he’s too easy a target for us critics to hit. Transformers especially took the storytelling methods of Armageddon to their worst extreme, invoking tropes in ways that I didn’t give a damn about.

You can hear my detailed thoughts on those three awful films, plus the fourth not-too-bad one, in the Now Playing Podcast archives.

I may be mostly drawn to films that do provide insights into characters and comment on everyday life though on-screen events. But sometimes I just want escapist entertainment. Armageddon delivers that in spades.

Tomorrow — 1999!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec