In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

Have you ever had the feeling that the world’s gone and left you behind….

More than any other form of art, films have a soul. Moviegoers can experience a picture on more than an intellectual level; sometimes there is a base, emotional connection. Watching a great film can be akin to falling in love.

This is a view I first articulated while reviewing Gus Van Sant’s 1998 remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho for Now Playing Podcast (part of our Fall 2012 donation drive, that review is no longer available). That film showed two talented directors could take the same script, sometimes even the same camera shots, and produce different results. One filmmaker created art that engrossed and thrilled audiences, while the other produced a rote, mechanical and generic film.

Tens, hundreds, or even thousands of people — depending on the scope of the production — come together to create a single experience for a viewer. Even I sometimes forget this; the auteur theory takes hold and I focus on the director as sole creator of a vision. While the director usually maintains creative control, sometimes even through the editing stages, the movie itself is the result of millions of little decisions made by every actor, set dresser, composer, editor, and cameraman on the production. With the right people involved even the most mundane script can become a memorable experience.

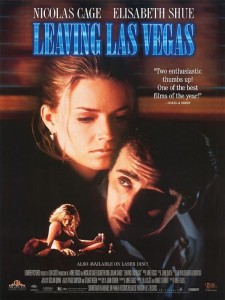

One prime example of such a script elevated by those working on it is Leaving Las Vegas, the 1995 drama directed by Mike Figgis, starring Nicolas Cage and Elisabeth Shue. On paper, this movie seemed like the most trite of stories — depressed drunk Ben Sanderson (Cage) is a Hollywood screenwriter whose penchant for drink has ruined his every personal and professional relationship. When he is finally fired from his job he is ready to die, so he takes the last of his cash to Las Vegas where Ben plans to drink himself literally to death. In Vegas Ben hires a prostitute Sera (Shue), the damaged hooker with a heart of gold. The two lost souls fall in love, yet neither is willing or able to change their self-destructive habits.

These character tropes are so hackneyed that I would expect this to be a film made in the 1930s, when stories and characters were broader, and not the 1990s.

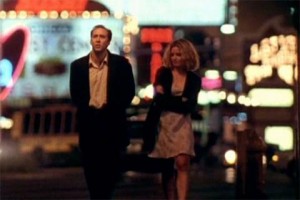

Cage in one of his more charming scenes, back-lit by the lights of the Vegas strip.

The film is based on a novel by John O’Brien. I have not read that book, but I have no doubt of O’Brien’s commitment to the material. Two weeks after discovering Leaving Las Vegas was to become a film, O’Brien used his gun to commit suicide. Clearly this was a man who understood the struggle with depression and the impulse to kill yourself. Yet, despite the insight his prose may offer, I have no interest in reading a book about two stereotypical characters going through a depressing endeavor. It may be very well written and I may be missing out, but the story itself sounds uninteresting.

Yet, despite cliched characters and a tired plot, in the hands of these filmmakers the result is a dramatically moving experience. Few movies I’ve seen in my life parallel the emotions stirred in me by Leaving Las Vegas, for what this team did, through filming and editing, was craft a film where the plot matters less and the characters matter more.

The tale is about a drunk, and the editing and filming often give the film a fugue-like ambiance. Sometimes the dialogue is crystal-clear, loud and in full focus. Other times the music mix raises. Sometimes you hear nothing as the actors’ lips move, other times there are words but you cannot make them out. It’s a dream-like experience that reminds me of techniques used by David Lynch.

The impact of the music cannot be overstated. The score, composed by Figgis himself, sounds like music played around 2 a.m. at an upscale bar. Heavy with piano and saxaphone, the music has a slow jazz feel that underlines the emotions of the moment. More, in an unusual move, some of the score is lyricized and sung by Sting. It blurs the line between soundtrack and score, but in the process creates sorrowful ballads of love and loss. Those original compositions intermix with covers of classic songs, such as “Lonely Teardrops” sung by Michael McDonald.

The sounds of the street often drown out character dialogue, to great effect.

The result sometimes feels like a depressing music video or an “in memoriam” montage, played while the characters still live. That Figgis is so willing to part with dialogue and just convey mood shows that in Las Vegas plot doesn’t matter. This is a character-driven story and we don’t need to hear their words to feel their pain.

This type of disregard for traditional narrative is used at the micro and macro scale. Sometimes the film cuts to the future suddenly, and we return to the present when Ben comes out of his stupor. We learn about the missing moments when Ben asks what happened. This is a movie told primarily from Ben’s shaky, out-of-focus point of view, and the camerawork and editing embody that mindset.

More than the cinematography, this film hops in and out of Ben’s own head. Sometimes we see Cage saying outrageous things, but then we discover it was only a fantasy in the character’s mind. In contrast, sometimes Ben makes equally offensive statements out loud and faces the very real consequence. As his blood alcohol content rises Ben cannot distinguish reality from fantasy, and, like Ben, the audience never knows exactly what is happening and what we can believe.

Of course, Figgis could not accomplish this alone. In the hands of a lesser actor than Cage Leaving Las Vegas could become an unintentional comedy quickly forgotten. Now, 20 years later, Cage is often disregarded, written off due to a long string of bad movies in which the actor makes unfortunate character choices.

Cage is an actor who gets off on playing characters in unconventional ways and giving them strange mannerisms. Often that will alienate the audience, but in Leaving Las Vegas Cage commits totally to the role. His body language exudes desperation. In one of the movie’s first scenes Ben is unintentionally sober, craving drink, and hitting up some colleagues for cash. He comes off sweaty, clumsy, and off-putting. One scene later, after a few drinks, Ben has an undeserved, over-inflated sense of self-confidence and makes improper advances on an attractive woman at the bar. It’s a wild swing of character, and is played perfectly through Cage’s intonation, eye work, and mannerisms.

This type of character could alienate audiences. Had viewers seen Ben as more creepy than sympathetic the result could be quite different. It’s little moments Cage plays, such as sobbing “I’m sorry” when being fired, that show humanity in this sad soul. It makes him someone we feel for, rather than pity.

I was a fan of Cage’s coming into Leaving Las Vegas, with Guarding Tess, Trapped in Paradise and Wild at Heart as highlights (though I’d also suffered through Kiss of Death, It Could Happen to You, and Amos & Andrew). Cage often gave captivating performances, but none I’ve seen before or since match his Oscar-winning performance here.

Despite how they meet, the relationship between Ben and Sera is about love, not sex.

Matching Cage’s portrayal is co-star Shue. In her roles in Back to the Future 2, Adventures in Babysitting, and even Cocktail I’d found the actress to be capable, but unexceptional. As Sera, Shue shows a range I’d never seen before. Early in the film Sera is a hooker, and very good at her job — she instinctively knows what the John wants, and becomes it. With Ben we see Sera start to open up. She lets down her guard, takes off her make-up, and becomes a real person. The transformation is startling, as is Shue’s lack of vanity in several unflattering scenes.

But Sera is not your normal streetwalker — she also has regular visits to a therapist. In these scenes we get to see inside Sera’s thoughts through monologues, confessions taken from her therapy session. As edited, these moments play like scenes from the confessional booth in MTV’s The Real World, but without them we would never be able to trust Sera. We never see the therapist; Shue is giving brief one-woman performances, but conveying pure emotion. This is a challenge for any actor, and she pulls it off. Shue fully deserved her Academy Award nomination for this performance.

Together Cage and Shue create a wholly believable, wholly dysfunctional, couple. Both broken characters are instantly drawn to the other. Though Sera knows Ben may be trouble, she puts that aside and chooses to follow her heart. The film avoids making their relationship too gross or base by actually, and believably, removing sex from the equation–while Ben hired Sera for physical gratification the liquor prevented him from performing. He becomes the only character not sleeping with Sera, even choosing to sleep on the sofa at night despite Sera’s repeated offers of more.

These two share a chemistry and a spark on screen that few romantic films can match. Though it’s a futile hope, it’s easy to root for these two to overcome their hardships through their new-found love.

Those two actors are the primary cast but even the minor roles are perfectly played by actors you’ll recognize; from Steven Weber (Wings, Stephen King’s The Shining), to comedian Richard Lewis, to Laurie Metcalf (Scream 2, Roseanne). It could almost be a drinking game — take a shot when you see an actor you know. With French Stewart, Shawnee Smith, R. Lee Ermey, Mariska Hargitay, and even, in the thankless role of bank teller, License to Kill’s Carey Lowell, you would be as drunk as Ben when credits roll.

No one on screen breaks the mood. Figgis has created his own Vegas, sometimes romanticized, sometimes demonized, but always real.

Leaving Las Vegas is a film with layers. On the surface, taken literally, the plot is about a terminal man and the woman who loves him as he dies. In such a bland interpretation, Sera is nothing but a fantasy, a female who serves a man’s needs. Sera describes herself as being instinctively able to become what her clients want, and she does that for Ben. Early in the film the drunk fantasizes of a woman pouring liquor on herself so he can drink off her, and she would have purpose. Ben never tells that to Sera, but she does that for him — alcohol and sex, Ben’s fantasy realized. Ben calls Sera, “my Angel”, and you could see her as nothing but.

Leaving Las Vegas is a film with layers. On the surface, taken literally, the plot is about a terminal man and the woman who loves him as he dies. In such a bland interpretation, Sera is nothing but a fantasy, a female who serves a man’s needs. Sera describes herself as being instinctively able to become what her clients want, and she does that for Ben. Early in the film the drunk fantasizes of a woman pouring liquor on herself so he can drink off her, and she would have purpose. Ben never tells that to Sera, but she does that for him — alcohol and sex, Ben’s fantasy realized. Ben calls Sera, “my Angel”, and you could see her as nothing but.

Yet to take that interpretation is to miss several important details. Sera is, in many ways, a mirror of Ben. Both came to Vegas from Los Angeles. Both are recently unemployed (Sera finding herself without purpose when Yuri, her lover and pimp played by Julian Sands, is murdered by Russian mobsters). Both characters are deeply wounded and on dangerous paths. And both accept each other unconditionally; Ben’s condition of being with Sera is that she never ask him to stop drinking. Likewise, Ben is accepting of Sera’s profession, knowing that she will continue to hook while he lives with her.

Finally, Ben’s course is a straight one. He starts and ends the film a drunk and he never waivers from his path of self-destruction. It would be nihilistic if his story was the only one in the film. Yet through loving Ben, Sera softens. The relationship forces Sera to mature, and she evolves from accepting her doomed relationship to trying to fix it, finally asking Ben to see a doctor. When Ben responds by bringing another woman home to her bed, she instantly kicks him out — she was not that strong when the movie began and she was working for Yuri.

Finally, Ben’s course is a straight one. He starts and ends the film a drunk and he never waivers from his path of self-destruction. It would be nihilistic if his story was the only one in the film. Yet through loving Ben, Sera softens. The relationship forces Sera to mature, and she evolves from accepting her doomed relationship to trying to fix it, finally asking Ben to see a doctor. When Ben responds by bringing another woman home to her bed, she instantly kicks him out — she was not that strong when the movie began and she was working for Yuri.

The star of the movie is clearly Cage as Ben, but every time I watch this film I become more convinced the true main character is Shue’s Sera. And it is through Sera that I found my own redemption in 1996.

That summer I had graduated college. My Communications degree and B-average in were not opening any doors. I had a small apartment in a boring town. Most of my friends had left for bigger cities and greater opportunities. My full-time job was working nights as tech support for an Internet company. It didn’t demand much; I sat alone in an abandoned building for eight hours a day, answering the phone on the rare occasion that it rang. It also didn’t pay much; I was living on $8.25 per hour.

Not that I had career aspirations. In college I spent my time doing my coursework and never got to the other things I wanted to do — write some screenplays or even publish some short stories. I had nothing to build my resume, and no idea what career path I should take. I still wanted to entertain people — that drive instilled since seeing Pump Up the Volume — but come fall, even my gig as a DJ would be taken away.

Despite having family living in my same town, we were never close. I preferred being alone in my dark apartment to spending time with them (and I loathed being alone). I was so desperate for friendly contact that, despite having graduated, I asked my college radio station if I could continue to work (for free) as a DJ through the summer.

Mostly, I was lonely. While friends would have alleviated this problem, to me the solution was a girlfriend. Many of my college friends had married soon after graduation. It is very easy for a lonely straight man to envision a woman as the answer to his troubles, and I certainly fell into that mindset. Yet with few friends, no social events to attend, and Internet dating not yet commonplace, I had no way to even meet a woman unless she happened to be delivering my pizza one Friday night.

With all these troubles, no money, few friends, bad job, no prospects, I was suffering from a deep depression.

I was never suicidal, but my overriding emotion was one of apathy, with a side of hopeless despair. My only pleasure in life came from movies. I couldn’t afford to see many in theaters, but I spent what little surplus income I had at the rental store week after week.

Ben’s constant fight against DTs show alcoholism isn’t a glamorous way to die.

That was when I found a kindred spirit in Ben Sanderson. Despite having recently turned 21, I was never much of a drinker. Still, there was something romantic in the very notion of going to Sin City and dying through copious consumption.

Yet through this act of destruction, Ben found his “angel” in Sera. And despite connecting with Ben’s depression, in Sera I saw strength and hope. Sera was in an equally bad situation — her “career” was short-term and dangerous. She was a smart, attractive woman, and even the Vegas cabbies were telling her she could do better than her station in life. When the movie ends Sera loses her love but gains hope for a brighter future.

Through Leaving Las Vegas’ trippy mood, moving characters, and tale of redemption I found my own. I was inspired out of my funk. Nothing happened quickly, but over the next four years my ambition redoubled, I went back to school to get a more employable degree, and I met my wife. But when my future seemed nearly as bleak as Ben’s, Leaving Las Vegas showed me the neon light at the end of a tunnel.

I believe that connection is partially because of the tragic, sad story presented, but the experience is heightened by Figgis’ choice to drop out dialogue and scenes. Figgis’ music created an emotional call-and-response; when the film’s dialogue was drowned out my own struggles filled in the blanks. When the dialogue faded out I would project my pain into the film, mixing with Ben and Sera’s until we were indivisible.

Even today, as I live a much happier, optimistic, and realized life, the film still moves me. You don’t have to be in pain to empathize with those in pain; you don’t have to hear their words to know their struggles.

This is where Leaving Las Vegas transcends being a movie and becomes a full, engrossing experience. This is the soul of a film.

Tomorrow — 1996!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec

Great insights! Not only the film but into your life. We have all been in that funk. The scene where Cage gets the final check from his boss and he says “I’m sorry” gets me every time. Plus having lived in Vegas my whole life, it’s like opening a yearbook to see Vegas from 20 years ago.