Welcome to Double Features, my ongoing column devoted to pairing a new theatrical release with a complimentary older title available on home viewing formats.

|

|

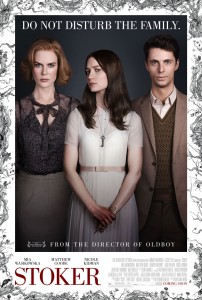

| Shadow of a Doubt | Stoker |

For March I’m fixing up stylish new thriller Stoker with 70-year-old Alfred Hitchcock classic Shadow of a Doubt for a double date that explicitly reminds audiences why it’s never a good idea for a girl to lust after her uncle.

Hitchcock movies pack a subversive punch because the director was so clever at sneaking taboo subject matter past his censors. Audiences in 1943 would merely have understood Shadow of A Doubt as the story of a gushing teenager (Teresa Wright) horrified to learn her visiting uncle (Joseph Cotton) is The Merry Widow Murderer. But savvier contemporary viewers will likely be creeped out by the closeness of their familial bond long before Uncle Charlie’s homicidal habits come to light. The nubile niece, also named Charlie, characterizes their connection as “telepathic”, but I’m closer to calling it out as incest.

Shadow of A Doubt isn’t one of Hitchcock’s more suspenseful or technically innovative pictures. The audience spends most of the run time waiting for its naïve star to deduce what they’ve known since the opening scene. But I suspect Hitch called it the favorite work of his career because it does such an expert job satirizing America and traditional Hollywood depictions of wholesomeness. Not only does a niece’s unbridled desire for her uncle go unnoticed in this seemingly upstanding small town, but common folk commiserate over speculation on how they might kill one another, banks profit from blood money, and perversion can be seen beneath the chipped paint of civility in every scene. The one false note of the picture comes when an FBI agent tries to assure the disillusioned young Charlie that people are basically decent and criminals like her uncle are the anomaly.

Stoker clearly invites comparisons to Shadow of A Doubt as it also introduces a homicidal Uncle Charlie (Matthew Goode) into the home of a blossoming schoolgirl (Mia Wasikowska), but takes the scenario one step further by suggesting the two share an inherited proclivity to kill. Dour young India certainly knows her way around a hunting rifle, and thinks nothing of silencing randy classmates with the sharp end of a pencil. But she’s a virgin when it comes to the ways of sex and murder, and spends most of the movie warming up to the idea that her father’s brother (and possible killer) has a lot he could teach her in these areas.

Stoker marks the Hollywood debut of acclaimed director Chan Wook-Park (Oldboy). Like Hitchcock, he’s come to America with a healthy dose of cynicism and an eye for subversive detail. Almost every shot in the picture simmers with Freudian possibilities – from the snaky removal of a belt used to strangle a man during intercourse to a spider crawling up the girl’s thigh as she plays a love song on the piano. These searing images perfectly capture the balance between suppressed desire and sociopathic bloodlust that hangs over our not-so-naïve star’s coming-of-age.

Hitchcock used the incest taboo to tease audiences about presumptions of innocence, but stops far short of nihilism and always delivers crowd-pleasing thrills. Stoker, by contrast, corrupts audiences by asking them to fully explore the darkly erotic possibilities of the uncle-niece union and resists reassurances of societal norms. I RECOMMEND both movies, and suspect viewers will get even more out of seeing them together. But you may not want to invite the family to watch along with you.