In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

In The 40-Year-Old Critic, Venganza Media creator and host Arnie Carvalho recalls a memorable film for each year of his life. This series appears daily on the Venganza Media Gazette.

As I did with my 1980 review of Popeye, I do feel the need to address the elephant in the room: how can my pick for 1999 be anything other than Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace?

It seems the likely choice. After 16 years a new, original Star Wars film was about to hit theaters, Lucas was directing for the first time in 22 years, and it was the top-grossing film of ’99.

Those who know me know how hyped I was for that film. I spent hundreds of dollars on toys and sat outside overnight in excessive rain, and later tremendous heat — third in line to get my ticket.

The Phantom Menace came and went, and when the year ended I realized the film had left me strangely unfulfilled. It defied expectations by actually making a Star Wars film boring. I have neither glowing nor damning things to say about Lucas’ return to directing. I’ll say this: It is certainly not a film that has impacted my life.

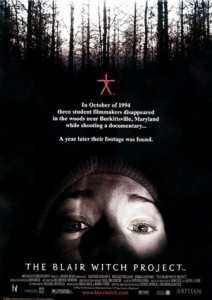

Instead, the film that stuck with me most from 1999 is not a big-budget Hollywood production, it is the smallest of films which became the year’s most profitable: The Blair Witch Project. I had never seen a movie like it before, and I’ll likely never experience one that way again.

The Blair Witch Project was more than a movie in 1999, it was a movement, and one that began months before it hit theaters.

I discovered The Blair Witch Project early in the year after reading about the film’s website, which was unlike any site I’d visited before. Odd and confusing, it told of Blair, MD, a town surrounded by superstition and mystery. I recall a timeline of events and some very low-res video. I also recall spending hours on this site, mostly waiting for the videos (which in today’s world would be tiny) to download to my 56kbps dial-up modem. The clips included news reports that seemed real enough, and introduced a mystery of three missing young people and rumors of the supernatural.

What the site didn’t mention was that it was all fictitious.

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to live in 1938, when an unsophisticated radio audience went into a panic over Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds? Or to be in 1974 and think there really was a chainsaw-wielding cannibal in Texas, instead of a story inspired by Ed Gein? The closest I will ever come to that is The Blair Witch Project. I found the site knowing of the film, but thousands didn’t — including some of my friends whose intellect I respected. They should have known better, but the age of the Internet hoax was not yet upon us.

This type of viral marketing is common now and thousands of movies have tried to replicate what Blair Witch innovated; but years before “viral video” was in our lexicon the Blair Witch website spread like wildfire via e-mails sent from person to person.

Josh and Mike begin their investigation.

From the presentation on the website, to the documentary-style filmmaking, it was very easy to be sucked into the “reality” of The Blair Witch Project. I watched as friend after friend fell for the ruse. Even as trailers for the film ran in theaters and on television, audiences weren’t sure if this was real.

“Don’t tell anyone,” I remember one friend confiding, “but I don’t think The Blair Witch Project is true.” I laughed and said, “Probably not, as I saw the lead actress on Jay Leno last night.”

Yes, even with a huge publicity push that involved multiple television appearances by the cast, audiences didn’t know what to make of The Blair Witch Project. That thousands of people could be so swept up in a shared fantasy, let alone one made by a few indie filmmakers and not Hollywood’s marketing machine, is phenomenal in the most literal sense of the word.

I went to see Blair Witch the weekend it opened. It had received so much acclaim in the media that I was excited to see the next evolution of horror. Plus I was curious; the website’s videos had asked many questions and I wanted to know the answers.

Initially I was put off by the filming technique. The early scenes introduce the three documentarians — Heather Donahue, Mike Williams, and Josh Leonard (all actors, but using their given names for the film) — as they set out to make a film about the myth of the Blair Witch. The early scenes have some comedic value and a bit of an eerie feel, but overall I wondered if I’d made a mistake. The shots seemed so amateurish and shaky. I knew this was low-budget filmmaking, but even in movies like Clerks and El Mariachi I’d never seen camera work like this — it felt like something I would shoot with my parents’ video camera and no tripod.

More, the characters seemed petty and dull. I knew they were actors, but they didn’t seem like very good ones. The bickering about a map, the various spats, I wondered when the horror would start.

But slowly the film sucked me in. Perhaps it was the first-person views, or maybe it was something instinctive — Heather’s constant cries for help breaking me down and stirring something primal inside me that is agitated by a female shriek. No matter, halfway through the movie, when Josh disappears, I was really invested in these characters and their plight. When Heather finds a small tied bundle and unwraps it I strained my eyes to see what was inside. There was blood and… were those teeth? Hair? It wasn’t gore like I was used to seeing; it was even more unnerving.

What… is… that?

By the time Heather, snot dripping from her nose, delivers her famous monologue to the camera I was totally taken. The Blair Witch Project did something no film had done since I was a child: it made me afraid. The tension of the scenes and the way it all felt so real; I had an uneasy feeling that I couldn’t just write off. The movie had gotten to me.

When the climax comes with Mike and Heather running through a house, then seeing Mike’s camera fall, I was dying to see more, to know more. Then, when Heather screams and her camera hits the ground and we see — is that Mike? Standing in the corner? I was enthralled, and frustrated. The film had provided no clear answers; what we saw could have been taken many different ways. But I had undergone the most exhilarating movie experience of 1999.

Among my audience I seemed to be the only one with that feeling. As credits rolled I witnessed something else I’d not seen before or since: a man around 50 stood up and shouted, “They must be pretty hard up for movies to put crap like that on the screen.” He left, disgusted.

That did not dampen my excitement. This was a movie unlike any I’d ever seen before, one that intentionally blurred the lines between fiction and reality (actors using their real names, regular citizens interviewed about a fictitious witch, etc.). More, the first-person filming technique had made me feel a part of the film.

According to Wiki, The Blair Witch Project was not the first “found footage” movie, but it was close, and it was the first that I had seen. Going in I had thought it unlikely I could find it believable that, in the midst of utter terror, these characters chose to keep the cameras rolling. Keep in mind this was before cell-phone cameras, YouTube, and the learned instinct of pulling out a camera every time tragedy occurs. Yet the way Heather, Josh, and Mike acted; their need for the security found through the camera lens, made me a believer.

That said, I thought it was a one-trick pony. Surely no film could pull this off again. How wrong I was. Blair Witch inspired a generation of filmmakers to try and replicate this formula. There were only seven “found footage” films released before Blair Witch; there have been more than 100 in the years since. Think about that.

Directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez were not trying to invent a new film style, they simply didn’t have the money for a full crew and improvised with actors, untrained in camerawork, filming each other. Yet now it seems impossible to escape this overused horror trope. I have seen so many “found footage” films, from Cloverfield to Chronicle to V/H/S to Diary of the Dead, and none have done it as well, or as believably, as Myrick and Sanchez did in 1999.

The scene you’ll never forget, and neither will Heather Donahue.

Initially I was drawn to Hollywood’s “found footage” trend, hoping to recapture that Blair Witch feeling. Now I avoid them at all costs, realizing the first was the best. In the end I like my movies to be cinematic. Blair Witch was a novelty but the constant output of more “found footage” movies has become a massive turnoff for me.

With Blair Witch as my first “found footage” experience I was shocked that my second wasn’t Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2.

Released the following year, I remember taking Marjorie to see it opening weekend. While nowhere near as inventive, original, or tense as the first film, there were aspects of that sequel I enjoyed. The post-modern idea of “The first film was a movie in this second film!” was novel, and the hard rock soundtrack was fun.

My love of Blair Witch continued, though the property continued to be watered down. I bought all three videogames, and even the Blair Witch action figure. Yes, McFarlane Toys made two figures of a character never seen on-screen.

I have since escaped the Witch’s spell. I sold the figures, and the games were a dull mess. I haven’t seen the sequel since its DVD release in 2001. Yet the Blair Witch Project is a film I still hold in high regard.

Tomorrow — 2000!

Arnie is a movie critic for Now Playing Podcast, a book reviewer for the Books & Nachos podcast, and co-host of the collecting podcasts Star Wars Action News and Marvelicious Toys. You can follow him on Twitter @thearniec